|

Research Subjects>EB concepts>Envirinmental Behavior>Schema/Affordance

|

Diversity of cognitive schemata for finding urban facilities Diversity of cognitive schemata for finding urban facilities

|

|

|

<20th International Association for People-Environment Studies, Jul. 2008>

|

| Ryuzo Ohno, Yurika Maeda |

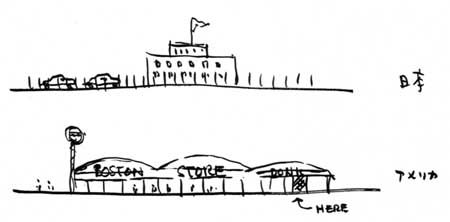

When trying to find an urban facility such as a station in an unfamiliar

place without a map or guide signs, we must rely on visual clues that we

associate with the destination. In other words, we are directed by cognitive

schemata that are theoretically shared by members of the same culture.

Although major cities in Japan are well modernized and seem quite similar

to Western cities, they still have cultural landscapes with latent clues

that are hard to detect for foreign visitors. Since Japanese recognize

most of these clues unconsciously, not even they can easily identify what

they are. Given rising globalization and growths in the number of foreign

visitors, however, a better understanding of differences in cognitive schemata

for locating destinations should prove useful toward making urban spaces

more navigable while preserving their cultural landscapes.

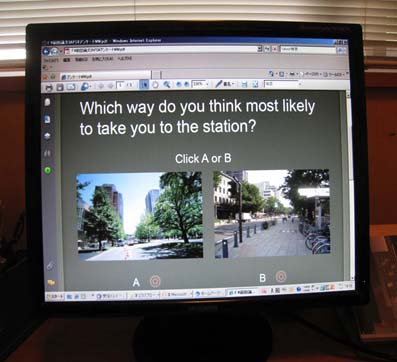

Our experiment thus sought to determine who shares what visual clues for

finding certain urban facilities. As stimuli for the experiment, photographs

of streets taken at various places in the Tokyo metropolitan area were

turned into composite images that were modified by adding or removing such

elements as sign boards, human figures, and roadside trees. Subjects were

then asked to rate each photograph according to the degree of likelihood

that the street leads to one of seven urban facilities: a station, a university,

a bank, a convenience store, a fast-food restaurant, a fashionable boutique,

and a government office. The subjects were university students with varied

cultural backgrounds (10 Japanese and 10 non- Japanese). After the session,

each subject was also queried about his/her way-finding strategies, selfevaluation

of performance in the experiment, and past living environments. The results

revealed that Japanese and non-Japanese subjects shared cognitive schemata

for some facilities (e.g., fast-food restaurants)—i.e., they clearly associated

the destinations with certain specific components (e.g., sign boards) or

general impressions (e.g., crowded small buildings) in a street scene.

There were also other facilities (e.g., universities) for which the Japanese

subjects shared cognitive schemata, while many foreign students did not.

This suggests that such facilities need to be provided with more guide

signs to assist foreign visitors.

|

|

Residents’ front/back definition of the spaces around suburban houses in Tokyo

Residents’ front/back definition of the spaces around suburban houses in Tokyo

|

<Book Chapter: in Martens, B. and Keul A. G. (Eds), Designing Social Innovation:

Planning, Building, Evaluation, Hogrefe & Huber Publishers, pp. 223-230,

2005.>

Ryuzo Ohno, Emiko Kubo |

Most suburban houses in Japan are built by prefabricated systems, and thus

they have quite similar appearances. The outdoor spaces around each house,

however, are arranged differently so that they mirror the resident’s personal

values and feelings (Marcus, 1995). The distinction between the domains

of “front” and “back” seems to play a fundamental role in determining the

layouts of such outdoor spaces as carports, yards, and gardens. Rapoport

(1977) points out that “There is much evidence that people very clearly

differentiate between front and back areas since very different symbolic

values are attached to them.” He also notes that the physical expressions

that symbolize front/back areas are very different across cultures.

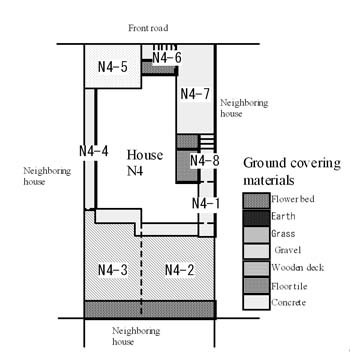

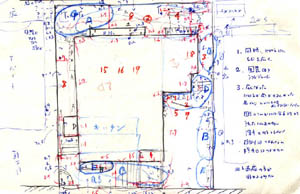

The present study was intended to give empirical support to the above argument.

A survey of 74 houses in the suburbs of Tokyo investigated how the residents

differentiated between front and back areas. Descriptions of the physical

features of the outdoor spaces as well as residents’ responses to a questionnaire

concerning their perception and use of those spaces were the data obtained

by the survey. We first drew a rough plot plan of each site visited and

asked the resident to point out the places where such activities as putting

out garbage, drying laundry and chatting with neighbors occurred. A list

of eighteen possible activities was prepared in advance and the item number

of each activity written down on the plan according to where it occurred.

We also probed for the resident’s perception of the spaces by asking which

parts they preferred to show neighbors and which parts they kept hidden,

which parts were thought of as front and which as back, and so on.

In order to analyze the data obtained, the outdoor spaces around each house

were divided into unit spaces according to such physical features as shape,

height and type of ground covering materials. We extracted 541 unit spaces

out of 71 houses; therefore the average number per house was 7.6 unit spaces.

Each unit space was analyzed according to such physical and spatial features

as size, location within the site, proximity to the street, accessibility

to the interior of the house, and visibility from neighboring sites.

Although about 30% of the unit spaces were not recognized as either, the

rest were distinguished as front (38%) or back (32%). Proximity to the

main thoroughfare and accessibility to the entrance and living room were

some characteristics of the unit spaces that tended to be seen as “front”.

On the other hand, the unit spaces seen as “back” tended to face a blank

wall or a door to the kitchen. As for the relationship between the front/back

distinction and residents’ use of the unit spaces, it seemed that such

activities as displaying plants and flowers or chatting with neighbors

occurred in the front while household activities and storage took place

in the back. Residents seemed to care better for the front region since

it is the part that communicates a public image. The back region was not

necessarily a deserted place, however, but could be a favorite place for

spending leisure time or conducting other private family activities. It

is interesting to note that drying laundry, which is believed as a typical

back-space activity, could be found equally in the front area according

to this survey. This could be simply due to the limited space in the back

area, but may also reflect the strong Japanese preference for drying clothing

and Futons (Japanese mattresses) in a sunny place, which tends to be regarded

as a front space.

Full paper → IAPS Book 2004

|

|

|

The

Relation between Schemata of Rooms in a House and Evaluation of Restfulness The

Relation between Schemata of Rooms in a House and Evaluation of Restfulness

|

|

<Summaries of Technical Paper of Annual Meeting of Architectural Institute

of Japan (E-1), Pp.773-776, Sep. 1997>

|

|

Takayuki Shimizu, Ryuzo Ohno

|

|

This study intends to clarify the hypothesis that the evaluation of restfulness

of a room depends on how it looks closer to observer's schemata. The study

conducted an experiment, in which 28 subjects were asked to evaluate 35

pictures of various home interior spaces according to its restfulness and

to judge their similarity to one's own image of one of such rooms as living

room, dining room, Japanese style room, bedroom and bathroom. As a result,

the hypothesis is generally supported by an average analysis although some

of schemata for a certain room are not shared.

The analysis of the individual subject's data reveals that even if the

score of evaluation differ among the subjects, each subject evaluates the

interior space according to one's own schemata. Thus the hypothesis is

more clearly supported by the individual analysis than the average one.

|

|